Cyberpunk 1: What's Cyberpunk?

Googling "cyberpunk," let alone "cyberpunk game," now hands you piles of Cyberpunk 2077 content. This pissed me off enough to write 5,720 words about it.

A lot of people now seems confused about what entails “cyberpunk” now, which, you know, thanks, CDPR.

Attempting to copyright the word “cyberpunk” is ironically one of the most corporate fuck-you moves a corporation could do, which is a big part of what cyberpunk is all about. But you wouldn’t know it from things like Cyberpunk 2077 and other properties whose take on cyberpunk seems to be “neon lights go brrrr.”1

Okay, so before I start trying to convince you to play video games, since someone (me) went and elected me president of cyberpunk, what is cyberpunk all about? What’s so good about it?

What’s cyberpunk?

Like any genre, it’s impossible to fully explain without adding a thousand caveats and doing a deep-dive on the historical context2, and that’s not the focus here. So to streamline this, I’m going to call out three core cyberpunk themes. As the president of cyberpunk, my executive opinion is that any cyberpunk media will go in hard on at least one of these.3

“Lawful” is not the same as “good”

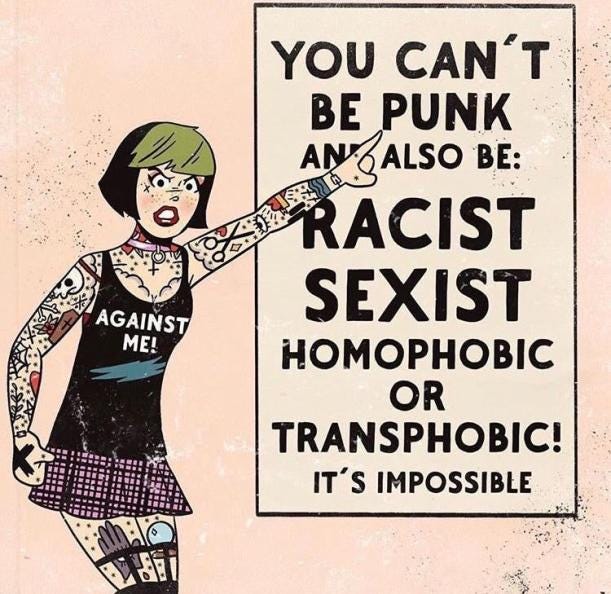

Cyberpunk protagonists are, almost without exception, antiheroes, criminals, and societal outcasts, people living outside the clearly-delineated social boundaries of the state. This is the punk half of cyberpunk: the power structures that shape our lives and our society are not good or justified unless they serve the citizenry. Power to the people, not over them.

Don’t forget: this is a punk genre (punk now watered down by cultural osmosis, but punk). It’s meant to say something about the world, to mean something, and to take a stance against power structures. Cyberpunk should never, by definition, be apolitical.

In cyberpunk, you usually see this theme manifest in the tools that the corporate state uses to oppress its people, such as omnipresent surveillance and the destruction of personal privacy; the power of money and lobbyists over democracy; and the capitalist commodification of the self.

It’s worth noting here as well that cyberpunk traditionally comes with the aesthetic packaging of neo-noir4, with chiaroscuro, Dutch angles, and paranoiac and subtly off-putting camera angles and techniques. (Neo-noir also has a lot of art deco and related influences.)

Visually, film noir is difficult to pull off in a game; it’s great for serving the drama of a film, but the visual traits that do this tend to be difficult to pull off in games for practical reasons. For example, chiaroscuro is amazing for leading the eye within a frame, when you can direct that frame… but when you can’t direct every frame, it can be distracting and muddy. It’s possible, but it requires a lot of care to pull off, and it’s not a good match for all types of gameplay, particularly those requiring players to quickly identify changing conditions in the environment.

So in games, you tend to see the noir aspects come through tonally. Noir genres generally embrace pessimistic settings with omnipresent, systematic corruption, where morality is relative, “doing the right thing” is irrelevant or even impossible, and everyone’s fatal flaws are on gallery-crisp display, which is another reason that cyberpunk protagonists are often antiheroes.

In noir, a crisp, black-and-white morality—the kind that produces “good guys” who never give into impulses or commit crimes—is generally impossible because of the societal framework a character finds themselves in, whether that’s simply being a victim of circumstance in an unjust world or succumbing to the dangers and vices of the niche you have built for yourself within it.

This broad idea carries through to cyberpunk: the stock setting, instead of a city rife with greed and corruption, is, uh… a city rife with greed and corruption. Cyberpunk is noir aged up a couple decades. It’s different; it’s matured with us alongside our technological, capitalist, deeply interconnected world. It follows the human vices of greed and systematic violence to their logical endpoint: a late-stage, unfettered, dystopian corporate capitalism, where all aspects of human life are commodified.

Late-stage corporate capitalism kills

Okay, so that’s the noir. Let’s talk about the cyber.

In most cyberpunk, you’re going to see technology condemn its users. I’m going to walk through three film examples.

In Akira (1988)—the first and probably best-known Japanese cyberpunk film in the States—excessive technological power is both painful for the empowered, whom it alienates and makes inhuman, and the society that he belongs to, which suffers leveled cities and civilian casualties. Blade Runner (1982)’s protagonist is a bounty-hunter of renegade artificially-engineered humanoids, and his interactions with them portray them as fundamentally human, reframing him as a murderer. In The Matrix, all of humanity is being outright harvested for energy while trapped in a virtual world.

I’m make examples of three of the more iconic and well-known cyberpunk films, so you could be forgiven for thinking a core theme of cyberpunk is the malevolence of technology, or even that cyberpunk is a fancy name for “dark sci-fi,” but while technology is often set up as an antagonistic force, this is usually explicitly framed as a moral failure: an inability to marry the technological with the humanist.

However, these three examples also demonstrate the inverse: When tech is married to compassion, it ceases to be a force for evil and instead becomes a liberator. That doesn’t mean that the evil facilitated with tech is undone, or unimportant; in fact, the harm generally outweighs the good, on a societal scale if not a personal one.

In Akira, the endgame antagonist is an extremely dangerous and nigh-unkillable esper capable of nuclear levels of destruction, but he’s a child. No advanced weaponry can stop or even match him, up to and including an orbital strike. What ultimately saves him and the world is the compassion of his friend and other esper children who essentially sacrifice their lives to stop the destruction and, in doing so, create a new universe. Blade Runner is far more personal in scope; the core theme of the ending is that artificial humans are fundamentally indistinguishable from “real” humans on an emotional level, and the protagonist and his artificial love interest have built a real, impactful relationship. The Matrix is the most straightforward example of the concept: the protagonist becomes the master of the technology that has trapped him and thus escapes it, ending the movie on a note of hope that he will liberate all humankind.

At this point, you may be wondering where I was going with the section header “Late-stage corporate capitalism kills.” Well, here goes—I’m walking through these examples to ask a question: If technology is inherently neutral, why consistently frame it as capable of great evil at all? What is the point of consistently framing it as destructive and hostile?

Let’s not beat around the bush here. In these examples as in most cyberpunk, the greater-scope villain is corporate and governmental greed and corruption. The problem isn’t solely that the technology exists—though in many cases, yeah, the technology shouldn’t exist and is inherently immoral in practice—it’s that society has allowed unfettered, immoral growth in the name of profit, power, and warmongering.

So here’s one final reframing. While Akira’s readily apparent antagonist is an esper child, the true villains are the proponents of the military research that created the esper children. Blade Runner’s antagonist is, more vaguely, the capitalist society that regards humans—artificial humans, but humans, who can think and feel—as disposable commodities. And while the villains of The Matrix are ostensibly the intelligent machines controlling humanity, the cause of the current world state was a global nuclear war culminating in an attempted genocide of artificial intelligences—an opponent whom humanity built for itself.

Technological advancement is not human advancement.

Cyberpunk is about the cyber, yes, technology’s influence on us twenty minutes into the future5, but the moral generally isn’t “technology is bad.” It’s that unfettered advancement is bad: Advancement for the sake of profit, advancement without regulation or guardrails, advancement without humanitarianism, advancement without caring about what it leaves behind. Tech in cyberpunk frequently also helps the disenfranchised when used ethically, especially when the work hits transhuman themes; it can be liberating, healing, and enabling. It simply needs to be placed in the hands of the oppressed, rather than the oppressor.

Transhumanism and self-determination

So when I say transhumanism can be “liberating, healing, and enabling” for the disenfranchised—that’s lofty. What does that actually entail?

Firstly: transhumanism. In the broad strokes, this concept is way older than cyberpunk—it’s older than what we consider “modern technology” at all—and it’s been framed as both ideal and folly for just as long.6 (Think Icarus’ wings.7) And, of course, since cyberpunk sets tech up as obstacles and technological transhumanism is, well, tech, transhumans aren’t always the good guys. (Not strictly cyberpunk, but think The Terminator.)

Obviously, there are ways that transhumanism can be yet another example of the above point, where the ubiquity of technology serves the ruling class rather than the citizenry. But for a disenfranchised cyberpunk protagonist, someone whom society doesn’t serve, technological advancements can be a tool for self-actualization.

Okay, so: Let’s talk about gender.

Cyberpunk 2077 got a lot of flak for the “Mix It Up” poster in its advertisement campaign, which depicts a feminine figure with the visible imprint of a penis. I don’t want to get too into this; it’s been since explained that despite CDPR’s transphobic track record, the art director responsible for the image intended to depict the in-universe exploitation of genderqueer bodies. I don’t disbelieve that, nor do I really care; within the greater written context of 2077, it’s simply not structured in a way that is authentically capable of being genderqueer. There are no neutral pronouns, the binary pronouns are connected directly to your voice, character customization is gendered, sex scenes are cisgender-centric, and while they’ve made a lot of noise about being able to decide whatever is in your pants, you don’t really see “what’s in your pants” in-world after character creation. It’s not that I want to see characters running around nude, obviously; it’s that, with no implicit trans inclusivity and no explicit trans inclusivity, having a genitalia option at all is a throwaway at best.

This is one of the reasons 2077 grinds my gears. It’s all of the aesthetics of the cyberpunk genre, all of the implied power of medical advancements such that the human body is infinitely customizable, but as spectacle; it’s a world where trans people exist, but firmly partitioned into the category of "weird cyberpunk details.” Yes, genderqueer people exist in this world but, like netrunners or ripperdocs, they surely aren’t here, playing our game.

I bring this up specifically to illuminate two things: How ubiquitous genderqueer concepts are in cyberpunk, to the point where a studio with a transphobic track record includes them almost reflexively; and to point out that mix-and-match genitalia does not actually scratch the surface of genderqueer or gender-nonconforming themes, only plays at them. So what can cyberpunk do here?

In genre-defining novel Neuromancer by William Gibson, razor girl Molly is an early example of technology used to defy gender conventions and roles. She is explicitly portrayed in the classically “male” position of being physically tough and unemotional, compared in the climax to exclusively male action heroes; her extensive cybernetic modifications make her the toughest character in the novel, up to and including the four-inch razors under her fingernails that make her a “razor girl,” framing her as a dangerous weapon. Emotionally, she prioritizes herself over others and is minimally empathetic; the most explicit example of her emotional unavailability is the literal cybernetic modification to her eyes that means she can’t cry. When explicitly asked how she can cry, she first says that she doesn’t cry much, then, when pressed, says the tears are routed into her mouth—she spits them out, an egregiously “unfeminine” behavior. (It could also be said that the modification of the female body is already taboo, given that the value of a woman’s body is often framed as being its purity.)

For a more widely-known example, director Lilly Wachowski has invited viewers to reconsider The Matrix through a trans lens following her acceptance of the GLAAD Media Award for Outstanding Drama Series for Sense8. The Matrix is a less explicit example than Sense8 (a soft sci-fi drama that deals explicitly with trans issues as well as other socially critical topics), but its story is deeply rooted in trans themes such as breaking out of false paradigms and affirming one’s freedom from control. Metaphorically, the characters who break out of the matrix are transhuman, confronting their lived physical reality and engaging with it on their own terms. The character Switch was additionally originally written to be explicitly transgender, feminine inside the matrix and masculine outside it. The matrix is an oppressive framework, but even then, those with power over the technology leverage it for their own liberation.

I’m focusing on queer representation here just to make the point, but there’s lots of room here for transhuman improvement of the lives of the disenfranchised. Science fiction has a lot of room to address disability, for example, in ways that don’t erase disabled lives, only enhance them. The majority of the games that I’ll mention in Part 2 have disabled characters, including characters who never “recover” from their disabilities, and characters with prosthetics for whom their prosthetics are neither treated as “just cool arms!” nor unnecessarily emphasized.

Listen, I’m not trying to blow smoke about how subversive and inclusive cyberpunk is; no genre is ever going to be an inclusivity monolith, and especially not a science-fiction genre that is dominated by men and was born in the eighties. Media will always have flaws. But, especially as we move forward into a more minority-friendly media environment, cyberpunk has a lot of open space to explore worlds where tech elevates us, enables us, empowers us. It lives in a space where we can explore the topic with nuance: tech as a tool of the ruling class to suppress the citizenry, hand in hand with tech as a tool of the citizenry to liberate themselves from the oppression of the ruling class. Since we’re living in something of a cyberpunk present right now, fiction can help us process these concepts and develop nuanced feelings about them—the neon and noir aesthetic gives us just enough of a barrier to step outside of ourselves.

Now what?

Now that I’ve completely gone off about what cyberpunk is, we can talk about some entries to the genre. Next week, I’m going to talk about cyberpunk games for the neophyte—a “tasting plate” to get a solid spread of what cyberpunk games have to offer.

Something I missed? Send me your questions, suggestions, and feedback here! Enjoying what I write? Why not subscribe?

For more on Cyberpunk 2077’s failings, you can check out this review on The Wired highlighting how superficial the world is, or this more neutral review on Polygon. Regardless, keep in mind that Cyberpunk 2077’s studio CDPR is notorious for mistreating its employees and treating them like disposable batteries, which is, ironically, kind of a core issue in cyberpunk.

Check out the TV Tropes page for a succinct summary and exploration of related tropes, if you’re into that kind of thing.

As a forewarning, I have not been a visual techniques purist while selecting the games that I’ll be talking about in Part 2.

Cyberpunk also overlaps a lot with tech noir, a term which was coined in The Terminator. Because this entry is already comically long and the genre distinctions can be so fine at times as to need a microscope, I’m not going to get into that here.

The distant future. The year 2000. (This is not a highly academic link.)

I’d like to add an important caveat just to cover my bases: Transhumanism is obviously not a universal good; the concept can also play into practices like eugenics. I think this falls into the “technology is morally neutral and can be used in good and evil ways” and “society’s callousness toward the disenfranchised” categories, but I wanted to be clear. Like all technology, its moral standing is determined by whether it serves the people or controls them.

Also in transcendentalist (or proto-transhumanist) myth, see Bellerophon, who attempted to join the gods on Mount Olympus and was struck blind as punishment, and the Fountain of Youth, which removes the human limit of mortality.